The

Gympie Gold Story: Exploring and Reopening A Historic Goldfield In Today's

Business Reality.

Ron Cunneen1 & Ian Levy2

ABSTRACT

Australia was built on gold and from 1850 until 1950, most of the gold came from reef orebodies in the historic goldfields of Eastern Australia. The old timers did not mine out all of the gold; why then are most of these goldfields lying dormant?

Huge quantities of gold remain unmined and largely unexplored because exploring and reopening historical goldfields is a business activity that generally does not suit today’s capital market requirements.

If we discover gold in these historic goldfields, it is often nuggetty and difficult to quantify prior to actual mining. This added uncertainty makes fund-raising for exploration in old goldfields very difficult.

Life and labour was cheap when the historical goldfields were being mined. Consequently, mining was labour-intensive and focussed on narrow-vein, high-grade orebodies. Modern mining is focussed on ore types that are conducive to mechanised mining and in general, the mining of -vein orebodies are unsuited to mechanisation. This technology-shift has also added to the difficulties of fund-raising for redevelopment of old goldfields.

The Gympie Goldfield was the first profitable redevelopment of an eastern Australian historical goldfield and reasons for its success include:

1. The entire goldfield and surrounding prospective

ground was owned by one company, Gympie Eldorado Gold Pty Ltd, a wholly-owned

subsidiary of public listed Gympie Gold Limited.

2. The city of Gympie and surrounding Cooloola Shire is proud of its gold mining heritage and is strongly pro-development.

3. Major gold companies Freeport and BHP invested the high-risk funds for the initial exploration from 1980 until 1991.

4. Major gold company BHP Gold invested the risk funds for the initial reopening of part of the goldfield and then departed the field in 1991.

5. Small-medium gold company, Gympie Gold Limited reassessed the historic data and the modern data and concluded that a viable gold mining business could be created by a careful investment of time and limited money:

· Investing a modest amount of capital to commence production;

· Investing in geological knowledge to enhance discovery rates over time;

· Reinvesting cashflows to build the business by discovery and development. The Gympie operation became a self-funding exploration play.

· Developing an integrated exploration continuum from mine exploration through to regional exploration. Exploration must have no demarcation between mine and non-mine activities.

6. Gympie Gold’s initial mine development was able to attract joint venture and debt funding for the mine expansion and mill construction because the gold in a major orebody, the Inglewood Reef, was fine-grained, reasonably predictable and continuous. This single orebody was amenable to the estimation of mineral resources and ore reserves and provided the “bankable” asset to underwrite expansion.

7. The capital markets supported Gympie Gold’s bold initiatives in 1999 to embark on expansion of the existing Monkland Mine whilst simultaneously developing a second exploratory mine, the Lewis Mine, based on inferred resources only.

8. The investment in geological and mining expertise

paid off in the recent discovery of new wide, high-grade bulk orebodies that

are ideally suited to modern mechanised mining methods.

This paper summarises the exploration strategies that succeeded in this setting and briefly sets out the current strategy to significantly expand gold production from Gympie.

Part 1 THE EXPLORATION SETTING

1.1

Introduction

The Gympie Goldfield is located 150km north of Brisbane. It has excellent infrastructure with easy access to highway and rail transport, power, water and workforce. Gympie Eldorado Gold Mines Pty Ltd (GEGM) owns the tenements over the Gympie Goldfield and surrounding exploration region. These permits cover an area of over 1300 square kilometres and surround our Monkland and Lewis Mines at the south end of the Goldfield. Historically the Goldfield was continuously worked for 60 years between 1867 and 1927. Hard rock production totalled 116 tonnes of gold (3.73 million oz) from 4.5 million tonnes of ore averaging 25.8 g/t recovered or about 29 g/t head grade.

1.2

Exploration History

The first modern exploration of the Gympie Goldfield occurred between 1980 and 1995, and was conducted by Freeport and BHP, under joint ventures with GEGM. The majority of that work concentrated on the ore reserve definition of the Inglewood Reef, on which the present Monkland Mine is based. Some first-pass, stratigraphic drilling was conducted elsewhere on the Goldfield, as well as some scout drilling on outlying historic workings.

From

1991 to 1995, GEGM started its exploration and development. Its first work was

to assemble all available historical records and attempt to devise a modern

geological interpretation. This study revealed unexpected results, including

the following key observations:

· The historic Gympie Goldfield paid dividends to shareholders that exceeded the capital invested across the entire goldfield. Most goldfields did not.

· Early mining produced gold from high-grade, narrow vein orebodies to a depth of about 250 metres. These bonanza grade “Gympie Veins” were exceedingly rich in visible gold and were mined by hammer-and-tap mining methods and processed by stamper battery, gravity recovery and mercury amalgam.

· The Inglewood Reef was “Low Grade” and difficult to process due to its fine grained gold. The Inglewood was only mined where it was near to shafts and was actively pursued, despite its long strike length (1.5 kilometres) and depth extent (1 kilometre).

· Mining at the southern end of the goldfield, from 1900 to 1927, introduced limited bulk mining methods using in-stope drills and exploited large stockwork orebodies up to 80 metres wide. In one block of ground 100 metres cubed, the old timers mined over 1 million tonnes of stockwork at +12 g/t grade. This indicated that big orebodies occurred at Gympie but within most of the goldfield, previous operators had ignored ‘big ore’ types.

· The gold-bearing rock units were concealed in over 50% of the goldfield and a lot of the concealment was “impenetrable” to the old-timers because they never introduced exploration drilling techniques into the Gympie Goldfield. Concealment arose from 3 geological situations:

1. The favourable “productive beds” dip 30 degrees eastwards and most are concealed by a limestone-shale sequence thrust over them. The old timers countered this by sequentially sinking deeper shafts to the east of successful shafts. Over 1500 shafts were sunk across the field but production rarely occurred below 400 metres depth due to pumping and ventilation limitations of the old shaft technology.

2. The favourable geology forms a recessive topography. In the southern and western areas, the favourable “productive beds” are concealed by the Mary River valley with 5 to 20 metres of sandy alluvium. The old timers simply could not handle water inflows so these areas were left largely untouched.

3. Pre- and post-mineralisation faulting has occurred throughout the field and in many instances, large blocks of ore were not found by the old timers who had no exploration drilling capabilities.

In 1995, GEGM felt the risk-reward setting was sufficient to justify further exploration and reopening of the Gympie Goldfield. This was the highest risk step of all and it appears to be paying off thanks to the flexibility and intense exploration focus of the company management, and to a modicum of good luck.

Part 2 THE ORE TARGETS

2.1 Goldfield

Geology

The Gympie Goldfield covers an area of 4km by 10km and consists of an extensive, mesothermal quartz vein system hosted within the Permo–Triassic mafic to intermediate island arc volcanics and sediments of the Gympie Group. The Gympie Group sits on a Devonian basement of deformed, deep marine, basalt, chert and sediments called the Amamoor Beds. These have been intruded by mid- to late-Triassic granite and diorite. The nearest intrusion to the Goldfield lies 10 km to the south east.

The upper units of the Gympie Group comprise the South Curra Limestone and shale beds of the Tamaree Formation. These upper units appear to be unmineralised.

Most of the high-grade mineralisation occurs beneath the limestone where the quartz veins are in contact with carbon-rich sediments, historically referred to as “The Productive Beds”. The Productive Beds lie above volcanic rock units and dip from 10 to 45 degrees to the east.

The mineralisation at Gympie occurs as low sulphide, quartz-carbonate veins that are often associated with carbonate-altered dolerite dykes. The gold occurs as free grains, which can be very coarse. Isotopic dating of the mineralisation gives a Triassic age.

A large proportion of the gold produced from Gympie has come from reefs that do not outcrop at surface and are totally concealed beneath the barren limestone. The miners of 100 years ago understood this, and had such confidence that they would sink deep shafts through barren limestone to the Productive Beds to find rich reefs that had no surface indication. The mineralisation continues past the old workings down the dip of the Productive Beds. Thin river gravels of the Mary River cover much of the field but the old timers would not risk sinking shafts anywhere near the river for fear of flooding.

The Goldfield is fragmented into a number of “Blocks” which have been shuffled up and down by later fault movement. In some cases this movement has exposed the veining in the Productive Beds at the surface whilst in other blocks the veins are concealed at shallow depth beneath the barren limestone.

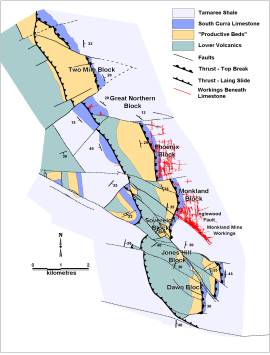

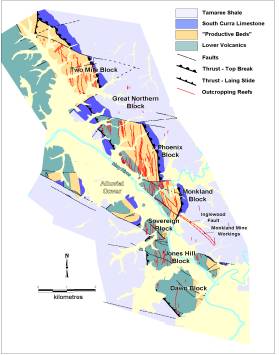

Geology of the Gympie

Gold-field. Alluvial

cover has been removed in the right hand map.

Figure 1

2.2 Gold Lodes

Four

main styles of quartz-gold lodes are recognised and are sumarised in Figure 2.

In a modern exploration strategy context, Stockwork and Inglewood lode styles

are the most significant exploration targets.

Figure 2

Gympie Veins

Gympie Veins

Gympie Veins are individual

tensional-style reefs 0.1 to 5m wide, which were mined within the carbonaceous Productive

Beds over a stratigraphic thickness of up to 60m. These reefs can be 1 to 2 km

long. Although some of these veins have a considerable vertical extent the

grades tend to be sub economic outside the Productive Beds. In the carbonaceous

areas the veins contain coarse free gold and often contain minor galena,

sphalerite and chalcopyrite. Average grade historically was 34 g/t Au. Gympie

Veins strike approximately north-south and dip west, roughly perpendicular to

the east-dipping bedding. Gympie Veins often come in groups of several veins

less than 100m apart. Individual veins have produced over 100,000 ounces and

the more successful historic mines exploited several of these veins at the same

time.

Break-style

Break-style

veins are bedding-parallel shears filled by quartz. They are often at the top

and bottom of the carbonaceous shales in the Productive Beds and are enriched

in graphitic carbon. The quartz is injected into these flat shears where

another more vertical vein comes in contact with the break. The quartz appears

to be diverted from its usual orientation along the break before jogging back

upwards to its normal position. Break-style quartz may run along the

intersection of the vein with the carbon-rich shear as a narrow ribbon for

several hundreds of metres.

These

zones of quartz have produced spectacular specimen stone, but tonnage is

limited. As stand-alone targets they are unlikely to produce million-ounce

deposits but because they often occur in conjunction with other vein styles,

they improve the grade. In the current Monkland Mine, break-style ore

represents only 15% of tonnes mined but produces over 20% of the gold.

Stockworks

Stockworks are wide zones of numerous thin, sub-parallel veinlets filling tensional zones with the same orientation as Gympie Veins. Stopes in the Scottish Gympie and Number 2 South Great Eastern Mines were over 30m wide, limited by economic cut-off grades of the time, (around 10 g/t Au). At today’s economic cut-off grades of about 3 g/t, the width of the stockwork in the Scottish Gympie mine is over 100m wide and up to 500m long.

Like the Gympie Veins they require the carbonaceous stratigraphy to maintain grade and therefore have a limited vertical thickness of up to 60m. Individually the thin stockwork veins are less than 10 cm wide but have much higher grades than the larger Gympie Veins. This may be due to the larger surface area of the small veins bringing the ore fluids in greater contact with carbon-rich wall rock. Stockwork veins can contain coarse free gold and are associated with arsenopyrite.

Individual stockwork orebodies containing over 0.5 million ounces can occur. This style of orebody is ideal for modern mechanised mining.

Inglewood

style

The Inglewood Reef is a large, sub-vertical, structure containing laminated quartz vein lodes hosted in a quartz-dolerite dyke formation from 0.5m to 6m wide, intruded by post-mineral, magnetic diorite dykes. The total width of the quartz and dykes within the structure is from 10 to 20m wide and extends over a strike-length of 2 km and a height of over 800m.

Continuous ore grade lodes within the Inglewood structure over substantial strike lengths and heights (100 to 800 metres). The panels of continuous ore are usually terminated where the late-stage diorite dyke has offset the lode channel by 2 to 20 metres across strike. The mining widths of the lode channels range from 1 to 7 metres averaging about 2.5 metres.

The grade of the Inglewood ore lode channels is variable. Whilst the Inglewood lode can locally grade above 1 oz/tonne (>31 g/t) it has an average grade of 7 to 10 g/t. The gold in the Inglewood is fine-grained and generally not visible to the naked eye. Historically, this lode-type was considered unattractive because of its “low grade” and low recovery rates when processed by gravity and mercury amalgam technologies of the past. Today’s mining and milling technologies achieve high efficiencies on the Inglewood lodes.

Unlike the other styles of quartz veins, the Inglewood structure does not require the carbonaceous stratigraphy to produce ore grades. The Inglewood Reef also differs from the Gympie Veins in that the strike of the structure is northwest. The Inglewood structure appears to terminate in an upward direction towards the Top Break (base of the limestone) where it splays and rolls over into what are termed “peel off” structures. The Inglewood does not continue through the Top Break into the limestone. Consequently the main Inglewood orebody is completely concealed by the barren limestone cover.

It appears that the Inglewood structure has acted as a feeder to some of the Gympie Veins and stockworks in the Monkland Block. Several Inglewood parallel structures exist elsewhere on the Goldfield.

The discovery of another Inglewood-style ore body could add over one million ounces of gold to the Gympie resource.

Part 3 RECENT

EXPLORATION FOCUS

Exploration from 1995 to 1997 focussed on mine exploration including resources and reserves, stope definition and discovery of new lodes within the accessible mine areas. A regional exploration team was assembled and from 1997 onwards conducted first-pass regional reconnaissance exploration and limited follow-up drilling which discovered many areas of gold mineralisation, including two large intrusion-related gold systems.

Key consultants were recruited into the “virtual company” of Gympie Gold. These key consultants included Garry Arnold, Roy Woodall (now a Director), Steve Webster and Greg Corbett but the guts of the exploration initiative came from the site team. And the company backed their initiatives as best it could.

Two years ago a start was made to evaluate the southern part of the Gympie Goldfield beneath the alluvial cover of the Mary River, south of the Inglewood Structure.

3.1

Exploration Beneath Concealment

In 1997-98, the outcropping southern portion of the goldfield was remapped – the first mapping in over 80 years. An airborne geophysical survey was conducted at the same time. This work revealed new structures and stratigraphy.

During this time, fresh rock chips were collected and accurately located. These samples were analysed for a wide range of elements including low-level gold. This testwork revealed that most gold orebodies in the Gympie Goldfield exhibit a primary geochemical halo extending some tens of metres. Fresh rock chip geochemistry has proven more useful in exploration than secondary geochemical halos in soil and stream sediments because the goldfield is heavily contaminated by 4.5 million tonnes of old tailings and millions of tonnes of mullock that had been distributed widely during and since historic mining.

A program of aircore drilling and fresh rock chip geochemistry during 1999 outlined 65 gold-in-bedrock anomalies and extended the “Productive Beds” south of the Inglewood Structure. So far only 16 of those anomalies have had scout drilling, and five of these areas have already provided significant drill hole intersections which require follow up. This work has demonstrated that there is potential for further discoveries in the Gympie Goldfield.

During the last year, the expansion of the Monkland Mine and development of the Lewis Mine decline has required most of our exploration effort to be refocussed into the near mine environment. As a result, large areas of the Goldfield to the north of the mine still require first-pass exploration and numerous targets, which have already been defined to the south, still require evaluation. The potential for further significant discoveries is high.

Part 4

CONCLUSIONS

4.1

Exploration Potential is Very Large

Ownership of the entire Gympie Goldfield has provided a large mineral endowment – approximately 4 million ounces of historic production with consequent excellent exploration potential to discover modern-styled company-building orebodies both within the mine environment and throughout the Gympie Goldfield.

The following table summarises the exploration potential of the currently known Gympie Goldfield based on the volume of unexplored prospective geology and the range of mineral endowments that have been encountered in the Gympie Goldfield:

|

Target Block |

Strike Length (kms) |

Block Width (kms) |

Block Height (kms) |

Block Volume (km3) |

Exploration Potential Range |

As Quoted in Public Statements |

||

|

Low Endowment |

High Endowment |

|||||||

|

Phoenix Block Deeps |

2.3 |

2.3 |

0.6 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

3.2 |

1.5 |

|

|

Mary River Valley |

6.5 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

4.9 |

2.4 |

5.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Great Northern Block |

1.5 |

2.5 |

0.5 |

1.9 |

0.9 |

1.9 |

1.5 |

|

|

Two Mile Block |

2.3 |

2.5 |

0.5 |

2.8 |

1.4 |

2.9 |

1.5 |

|

|

|

13km |

2.2km |

0.5km |

13km3 |

6M ozs |

13M ozs |

6M ozs |

|

The order-of-magnitude potential of the unexplored blocks in the goldfield exceeds 6 million ounces. It will cost about A$25 million to complete the first phase of the proposed exploration program. If this initial phase of exploration only discovers 1 million ounces of gold, it would represent a discovery cost of A$25 per ounce, which is still cost-effective.

4.2 Investment

Setting

In a modern exploration environment, it is not sufficient to have exploration potential. A clear strategic view and the human/financial resources to achieve the objectives are also required. A track record of success will also be helpful.

Small Companies Use Time More Than Money to Succeed

If the annual exploration budget is small, this work takes time and requires intense focus on detail. This may be an investment environment only suited to the most tenacious, small-medium sized mining and exploration companies. The reason for this is that many discoveries of new ore made during the reopening of historical goldfields are incremental and only small-medium companies can achieve positive returns for shareholders from incremental increases in resources and reserves.

The following table demonstrates how this was done at Gympie:

Monkland Gold Mine, Gympie Production & Reserves History

|

Year to |

Tonnes Milled |

Grade Milled |

Ozs in Ore

Milled |

Ounces in

Resources |

Ounces in

Reserves |

|

1994 |

16,024 |

4.50 |

2,318 |

174,000 |

0 |

|

1995 |

56,141 |

4.58 |

8,269 |

518,000 |

0 |

|

1996 |

118,300 |

4.78 |

18,201 |

470,000 |

127,000 |

|

1997 |

111,399 |

7.67 |

27,471 |

473,000 |

149,000 |

|

1998 |

112,676 |

9.24 |

33,473 |

468,000 |

142,000 |

|

1999 |

134,047 |

8.50 |

36,633 |

598,000 |

182,000 |

|

2000 |

138,500 |

7.80 |

36,750 |

571,000 |

197,000 |

Since GEGM commenced active exploration in 1994-95, discovery costs have averaged $A16 per ounce of gold in resources which is 25% less than the national average.

The philosophy adopted by Gympie Gold Limited has been to first establish a small gold mine with attendant infrastructure and technical skills. From this base, exploration success has been used to increase mine production and profits – in effect, a self-funding exploration program.

The ultimate objective was to reinvest operating cashflows in the short-term and maintain reasonable shareholder returns while pursuing opportunities for exceptional returns that would arise from reopening the significant Gympie Goldfield to its full potential.

Larger Companies Can Use Money to Succeed?

If the annual exploration budget is large and, if the necessary attention to detail can be maintained, this work can be done faster and can generate multi-million ounce discoveries on a scale required by bigger companies. To date however, few large companies have succeeded in this large-scale approach to the historical goldfields. Most large companies have become frustrated long before the detailed knowledge starts to bear fruit. Many large companies feel they have better targets within their exploration portfolios to invest their shareholders’ funds.

Larger companies may achieve better results by acquiring the knowledge already accumulated by smaller companies over time rather than spend too much time generating that knowledge from a zero base. We are only just starting to see this acquisition approach by larger companies emerging.

If this business is so

damn good,

how come there ain’t more people in it?

Ron Cuneen's 2002 paper at the Exploration in the Shadow of the Headframe - 2002 Symposium

Gympie Gold CEO Harry Adams - "The Gympie Gold Growth Phenomenon " at the Sydney Mining Club at SMEDG