DISCOVERY OF THE CADIA RIDGEWAY GOLD-COPPER PORPHYRY DEPOSIT

John Holliday, Colin

McMillan and Ian Tedder,

Newcrest Mining Limited, Exploration

Department, 1460 Cadia Road, Cadia via Orange, NSW, 2800.

Key Words: Cadia, gold, copper, porphyry,

drilling, magnetics, induced polarisation

Introduction

Introduction

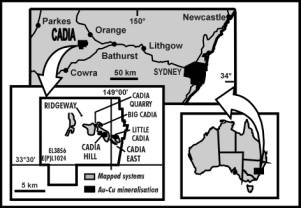

![]() The Cadia Ridgeway deposit is one of

a group of porphyry-style deposits discovered since 1992 by Newcrest geologists

(Wood and Holliday, 1995; Holliday et al, 1998), at Cadia 20 kms south of

Orange in the central tablelands of NSW. The Ridgeway deposit lies 500m below

the surface, 3 kms north-west of the Cadia Hill open cut mine, and was

discovered in November 1996. It is notably rich in Au with an inferred and

indicated resource of 44 Mt at 2.6 g/t Au and 0.82% Cu, and is currently under

development as an underground mining operation.

The Cadia Ridgeway deposit is one of

a group of porphyry-style deposits discovered since 1992 by Newcrest geologists

(Wood and Holliday, 1995; Holliday et al, 1998), at Cadia 20 kms south of

Orange in the central tablelands of NSW. The Ridgeway deposit lies 500m below

the surface, 3 kms north-west of the Cadia Hill open cut mine, and was

discovered in November 1996. It is notably rich in Au with an inferred and

indicated resource of 44 Mt at 2.6 g/t Au and 0.82% Cu, and is currently under

development as an underground mining operation.

Geology

The Cadia deposits are part of a Late

Ordovician – Early Silurian porphyry alteration-mineralisation system that

extends over an area of at least 6 X 2 km within the Ordovician Molong Volcanic

Belt of the Palaeozoic Lachlan Fold Belt (Newcrest Mining Staff, 1997). The Molong Volcanic Belt comprises a suite

of intermediate to basic volcanics, volcaniclastics, comagmatic intrusions, and

limestones. The suite is probably part

of a subduction-related island arc disrupted by later tectonism (Glen et al,

1997). In the Cadia area the volcanics

and intrusions are shoshonitic (Blevin, 1998).

Mineralisation styles at Cadia include sheeted

quartz vein, stockwork quartz vein, disseminated and skarn, all of which are

genetically related to a relatively small (3 X 1.5 km in outcrop) composite

intrusion of predominantly monzonitic composition, with a monzodioritic to

dioritic rind (Cadia Hill Monzonite).

The Cadia Hill Monzonite intruded Forest Reefs Volcanics

(volcaniclastics, lavas, subvolcanic intrusions, and minor limestone) and

Weemalla Formation (siltstone, mudstone, minor volcaniclastics). Emplacement of the Cadia Hill Monzonite was

probably facilitated and localised by the development of a major north-west

(NW) to south-east (SE) trending dilational structural zone, which is well

evident in magnetic data. The Cadia

deposits, including Ridgeway, are aligned in this zone.

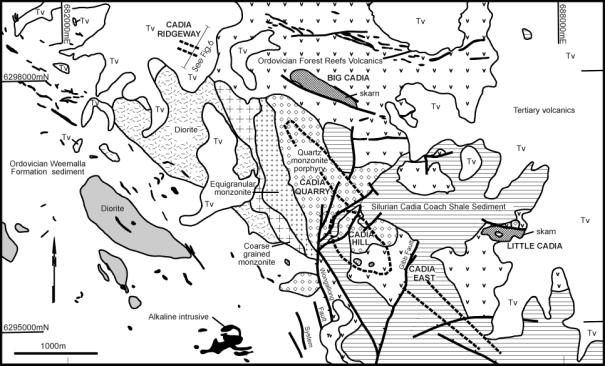

The Ridgeway deposit is an upright bulbous body

of stockwork quartz veining zoned about a small (50-100 m diameter) plug of

Cadia Hill Monzonite porphyry (Newcrest Mining Staff, 1998). The plug has intruded relatively flat-lying,

conformable Forest Reefs Volcanics and Weemalla Formation to the west of the

main Cadia intrusion. Spatially related pre-mineral intrusions include

monzodiorite and pyroxene porphyry dykes.

The most intense stockwork veining and alteration, and the highest Au

and Cu grades occur immediately adjacent to the monzonite porphyry. The best part of the orebody occurs above

the porphyry and the weaker parts along the sides. The intensity of veining and alteration declines both outwards

and inwards from the monzonite porphyry margin. This results in a small low-grade central portion in the

monzonite porphyry. Ore minerals are

native gold, chalcopyrite and bornite, mostly occurring within veins, but also

disseminated. Magnetite is a major

accessory mineral in veins.

Hydrothermal alteration associated with the strongest mineralisation is

potassic: orthoclase,

albite, actinolite, magnetite, biotite. This is overprinted by later propylitic

assemblages: epidote, chlorite, Fe-carbonate, calcite, hematite dusting. Structures cutting the mineralisation had

significant

pre-mineral movement with the conformable

Forest Reefs Volcanics-Weemalla Formation contact off-set by ±130m on a NW-SE alignment. However there was little syn or post-mineral

movement, since the mineralisation has no major offsets. The northern edge of the deposit is cut by

the North Fault, a vertical, NW-SE aligned structure along which a pre-mineral

pyroxene porphyry dyke was intruded.

Ridgeway is a small porphyry mineralisation system subsidiary to a

larger system, and is thus comparable to the Goonumbla porphyries (Heithersay

et al, 1990), also in the Lachlan Fold Belt.

Most significantly from an exploration

viewpoint Ridgeway lies 500m below the surface, at a site covered by

Miocene-aged basalt flows, 20-80m thick.

Beneath these flows there is a palaeo-weathered surface on the Forest

Reefs Volcanics (±20m of oxidation and another ±30m of leaching). Strong alteration and anomalous metal values related to the

deposit do not extend upwards for sufficient distance to be detectable at or

for a considerable distance below the palaeo-surface.

Early Exploration

Modern era exploration at the site was prompted

by its proximity to the mineralised Cadia district, and particularly by the

recognition of magnetic features, which can easily be interpreted as westward

extensions or repetitions of the magnetic anomaly over the magnetic skarn at

Big Cadia. In 1985 Homestake Australia

drilled two RC percussion holes to downhole depths of 95m to test magnetic

targets, with very poor results. In

1991 Newcrest drilled seven further RC percussion holes to downhole depths of

42-90m to more comprehensively test the magnetic targets, also with very poor

results. All these holes intersected

magnetic volcanic rocks, which were considered to explain the magnetic

features. In part they did, but none of

them went nearly deep enough to encounter any mineralisation.

Discovery: lead-up work

Discovery: lead-up work

In late 1992 the Cadia Hill deposit was discovered and at the same time an extensive halo of low-grade mineralisation was delineated to the NW of the deposit at Cadia Quarry. These results confirmed the NW to SE alignment of mineralisation at Cadia so step-out drilling was continued in both directions. Most importantly this drilling was conducted in a manner suited to the discovery and delineation of large mineral systems, with core holes typically 300-600m in length on 200m step-outs. Almost immediately the Cadia East deposit was discovered east of Cadia Hill. To the NW the Cadia Quarry mineralisation was found to extend for about 1 km, beyond which there was barren intrusive and volcanics both in holes and on surface. A further 1km NW the basalt cover begins.

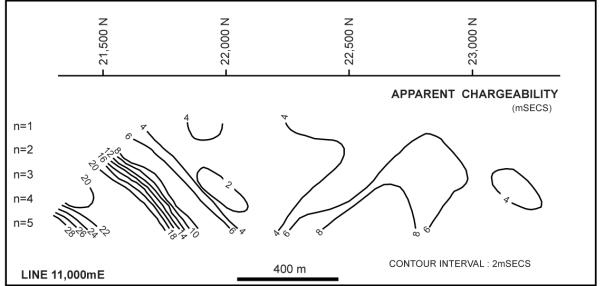

In an attempt to focus the exploration drilling NW of Cadia Quarry a regional reconnaissance IP survey was conducted in spring 1994. This survey used a 200m dipole-dipole configuration after orientation surveys had shown that the method could detect both the outcropping, but very low sulphide Cadia Hill mineralisation, and the covered (60-200m), high sulphide Cadia East mineralisation. The 200m dipole spacing was found to be necessary for both the depth penetration and lateral coverage needed over large mineralised systems. The aim of the new survey was to detect large, deep bodies of disseminated mineralisation, which it was expected would only show up at the bottom of the chargeability pseudosections. The survey obtained only one anomaly with these expected characteristics and which could not be explained by lithological contrasts. This was at, and east of, the Ridgeway site on three 200m spaced traverses. The anomaly was particularly attractive because it lay on the NW-SE alignment of mineralisation. Recent modelling work has suggested that the IP did not detect the Ridgeway high-grade ore because it is too deep. It is currently thought that it detected a disseminated pyrite halo above the ore. Whatever it actually detected the IP survey was important because it encouraged drilling sooner, in what turned out to be the right place.

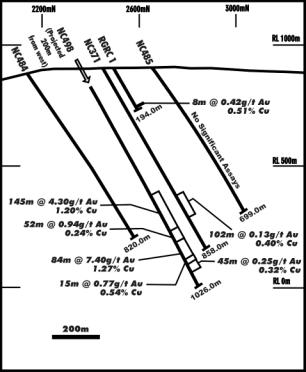

In February and March, 1995 two fences of RC percussion holes to 200m downhole

depth were drilled to test the IP chargeability and mineralisation corridor

target. The first of a total of nine

holes (RGRC1) obtained the most significant result: 8m at 0.42g/t Au and 0.53%

Cu from 182m, but there were 27 other narrow intercepts of +0.10g/t Au in the

holes. The RGRC1 intersection is now

known to be due to an extreme outer halo ‘leakage vein’ above the Ridgeway

deposit. The RC holes intersected

magnetic diorite or volcanics with >0.5% disseminated pyrite which was

thought at the time to explain the IP effect.

One of the western holes intersected anomalous Zn. It was possible to interpret a coherent

alteration-metal zonation pattern from the holes, which implied that there

might be a mineralised body at greater depth.

This was regarded as a bit of a ‘long shot’ at the time, but a deep hole

behind RGRC1 was planned.

![]()

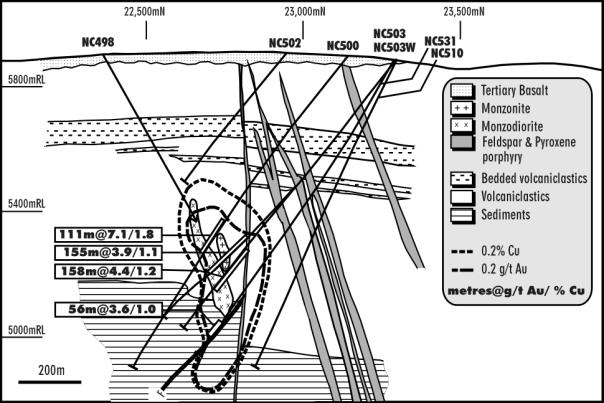

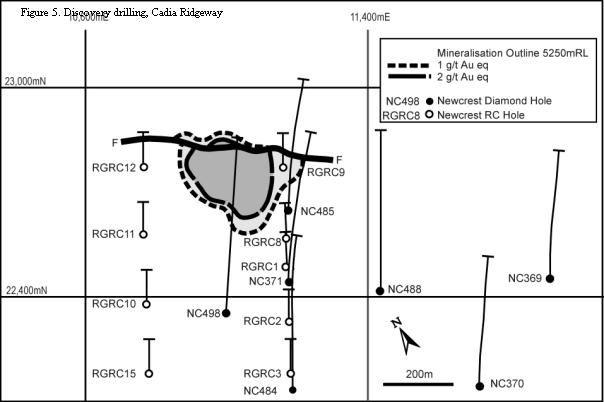

At the same time as the RC percussion drilling was in progress a fence of wide-spaced core holes (NC’s 368-370) was drilled to 500+m downhole depth, across the NW-SE mineralisation trend at a position one kilometre to the east of Ridgeway. It was considered at the time that none of these holes had obtained significant intersections of mineralisation, but the presence of encouraging alteration, particularly hematite dusting of feldspars was noted. In June 1995, as a continuation of this program, core hole NC371 was drilled beneath RGRC1 to a downhole depth of 513.6m. There were no obviously ‘ore grade’ intersections so logging and assaying were delayed while priority was given to work at Cadia East and around Cadia Hill where feasibility study deadlines had to be met.

The NC371 assays were received in November 1995 and were reviewed in January 1996, along with the results of NC368 to NC370, as a prelude to further drilling in the area. They showed a zone of increasingly anomalous copper mineralisation (118m at 0.10%) from 396m to the end of the hole similar to the Cu signature observed adjacent to the Cadia Hill orebody, plus several narrow +1g/t gold intercepts including 1m at 5.68g/t Au from 359m and 2m at 10.6g/t from 410m. Narrow higher-grade Au intersections in NC’s 369 and 370 (such as 1m at 7.30g/t, 1m at 6.52g/t, and 2m at 6.98g/t) were also recognised as being significant. The narrow higher-grades were given a greater significance than they had previously because it was being increasingly recognised at that time that a higher grade ore discovery at Cadia could be vital for the Cadia Project’s economic viability. Based on the review of the drilling it was decided that NC371 should be deepened.

![]()

Discovery: Getting Closer

NC371 was deepened to 858.4m in February 1996. The deepened hole intersected chalcopyrite-bearing, sheeted vein style mineralisation from 610-711m. This mineralisation compared very well visually with similar style mineralisation at Cadia Hill and was considered immediately to probably be a new discovery. However assays showed that the vein zone carried very little gold: 610-712m at 0.13g/t Au and 0.40% Cu. The vein zone was terminated by a fault, below which several narrow higher-grade intersections were made: 1m at 2.44g/t Au from 726m, 3m at 3074ppm Cu from 733m, and 3m at 4.49g/t Au from 809m. The results were considered encouraging and it was decided to drill more deep core holes around NC371 along the NW-SE mineralisation trend. It is now known that NC371 had penetrated the halo to the high-grade Ridgeway deposit.

Holes were immediately drilled 350m south (NC484), and 175m north (NC485) of NC371 but the vein zone was not intersected. In May 1996 NC488 was drilled 275m east of NC371 and intersected broad Cu anomalism. It was a logical decision to drill across the mineralised trend, and then back towards other known mineralisation before drilling to the west, which is where the deposit proved to be. With the benefit of hindsight we also know that the step-out spacings for these holes was too large; in fact NC484 was deepened after the discovery to intersect the deposit.

![]()

It was decided after drilling NC488 to review the results before conducting

more drilling around NC371, but it was already recognised that the best

potential lay to the west. By this time

wet mid-winter ground conditions meant that drilling had to be postponed until

the spring anyway.

![]()

Discovery Hole

The precise siting of the discovery hole (NC498), 175m west of NC371, was made using a structural interpretation of the results from existing holes, supported by the results of the interpretation of a heli-mag survey flown in autumn 1996.

The structural interpretation was that the fault cutting off the vein zone in NC371 would be much deeper to the west, thereby allowing space for a much thicker vein zone if the zone extended westwards along the strike direction determined from measurements on NC371 core. It was predicted that the vein zone would be intersected at 550m downhole, and this proved to be very accurate.

The magnetic interpretation took account of a better understanding of the significance of magnetite alteration effects on the magnetic anomaly patterns. The magnetic features at Ridgeway were re-interpreted as being largely caused by alteration magnetite rather than primary magnetite and it was recognised that NC371 had drilled into an east-west cross-cutting magnetic low, which might be related to the mineralisation. The site selected by using the structural interpretation was in a suitable position to test this low.

By November 1996 the Ridgeway site was dry enough to allow access so hole NC498 was commenced. It intersected two zones of very high-grade, porphyry stockwork mineralisation -- 145m from 598m at 4.30g/t Au and 1.20% Cu; and 84m from 821m at 7.40g/t Au and 1.27% Cu – and the deposit was discovered.

What Followed

The early post-discovery drilling included a

scissors hole and 200m step-out holes to the west. At first it was thought that the deposit could be of the same

scale (plus one hundred million tonnes) as Cadia Hill and Cadia East. However, it was quickly realised that

Ridgeway was smaller, but of far higher grade than the other Cadia

deposits. The deposit was drilled on 50

m sections from surface to inferred resource status by October, 1997, and to

indicated and inferred resource status by July, 1998. The geological interpretation of the deposit changed as more data

came available, with the description above being for the July, 1998 resource

estimate. By June, 1999 a decline

allowed access to the ore.

Conclusions

Ridgeway was discovered not just beneath 20-80m

of Miocene cover, but also some 450m into the Ordovician host-rock

sequence. It would not have been

readily detectable on the Ordovician surface by any mapping or geochemical

technique in the absence of the Miocene cover.

It is also very uncertain whether any geophysical technique would have

detected the deposit in the absence of the Miocene cover. It is debatable whether the 1994 IP survey

really detected the deposit and further investigation into this is warranted. The deposit is not a conductor and was not

detected by post-discovery downhole EM, even in a hole through the ore. The magnetic response at surface from the

magnetite in the deposit veins is lost in the noise caused by stronger, nearer

surface magnetic sources, which include the primary and alteration magnetite in

the host volcanics and the monzodiorite.

In fact, the deposit occurs in a relative magnetic low because of this

juxtaposition of magnetic sources.

There is no reason to suspect that gravity methods would detect the

deposit since the density contrasts of the host lithologies are very small.

Drilling was the main discovery technique for

Ridgeway. This may seem a statement of

the obvious, since drilling is involved in nearly all discoveries. However, the deep drillholes leading up to

the discovery, were specifically drilled in a partly ‘stratigraphic’ sense to

search for the geochemical and alteration vectors to a deposit. Hussey and Bernard (1998) describe a similar

use of drillhole information leading to the discovery of the Porphyry Mountain

Cu-Mo deposit in Canada.

As exploration of any terrain matures it

becomes increasingly important to explore the third dimension. In exploring at the depths at which Ridgeway

was found, drilling is clearly the best, and mostly the only option

available. To improve the value of deep

drillholes there is a pressing need for more developments in downhole

geophysics techniques other than EM, for the detection of off-hole,

non-conducting, but possibly polarisable and/or magnetic and/or dense bodies.

The most significant factors leading to the

discovery of Ridgeway include, firstly the use of exploration techniques

appropriate to the scale/style of the target being sought. The drilling and geophysics used were able

to effectively search for and delineate the metal and alteration zonation

patterns of the large Cadia mineralised system in all dimensions, particularly

at depth.

Secondly, the recognition of the significance

of the Cadia mineralisation system encouraged persistence. There was so much ‘smoke’ there just had to

be more deposits in the vicinity.

Thirdly, the ongoing enthusiasm and financial

support for the exploration process from the Board level down, was vital. It was recognised that Newcrest needed Cadia

to become bigger and better since it was the key to the immediate future of the

Company.

References

Blevin, P., 1998, A re-evaluation of

mineralised Ordovician intrusives in the Lachlan Fold Belt: implications for

tectonic and metallogenic models. Geological Society of Australia Abstracts No

49, p43.

Glen, R.A., Walshe, J.L., Barron, L.M. &

Watkins, J.J., 1997, New model for copper-gold deposits in Ordovician

volcanics. Minfo No 56, NSW Department of Mineral Resources, Sydney.

Heithersay, P.S., O’Neill, W.J., van der Helder,

P., Moore, C.R. & Harbon, P.G., 1990, Goonumbla porphyry copper district –

Endeavour 26 North, Endeavour 22 and Endeavour 27 copper-gold deposits, in

Geology of the Mineral Deposits of Australia and Papua New Guinea (Ed. F.E. Hughes) p1385 (AusIMM, Melbourne).

Holliday, J.R., Wood, D.G., McMillan C.C.,

Tedder, I.J., 1998, Discovery of the Cadia Au-Cu deposits, Lachlan Fold Belt,

Australia. Pathways `98 Extended

Abstracts Volume p74, British Columbia & Yukon Chamber of Mines, and

Society of Economic Geologists.

Hussey, J. and Bernard, P., Exploration of the

Porphyry Mountain Cu-Mo deposit. Mining

Engineering, August, 1998.

Newcrest Mining Staff, 1997, Cadia gold-copper

deposit, in Geology of Australian and Papua New Guinea Mineral Deposits (Eds.

D.A. Berkman & D.H. Mackenzie) p641. (AusIMM, Melbourne).

Newcrest Mining Staff, 1998, Cadia gold-copper

deposits: geological update. Geological Society of Australia Abstracts No 49,

p334.

Newcrest Mining Limited, Various internal

memoranda and monthly reports written between 1994 and 1999.

Wood, D.G. & Holliday, J.R., 1995,

Discovery of the Cadia gold-copper deposit in New South Wales – by refocussing

the results of previous work. New Generation Gold Mines: Case Histories of

Discovery, Australian Mineral Foundation, Adelaide.